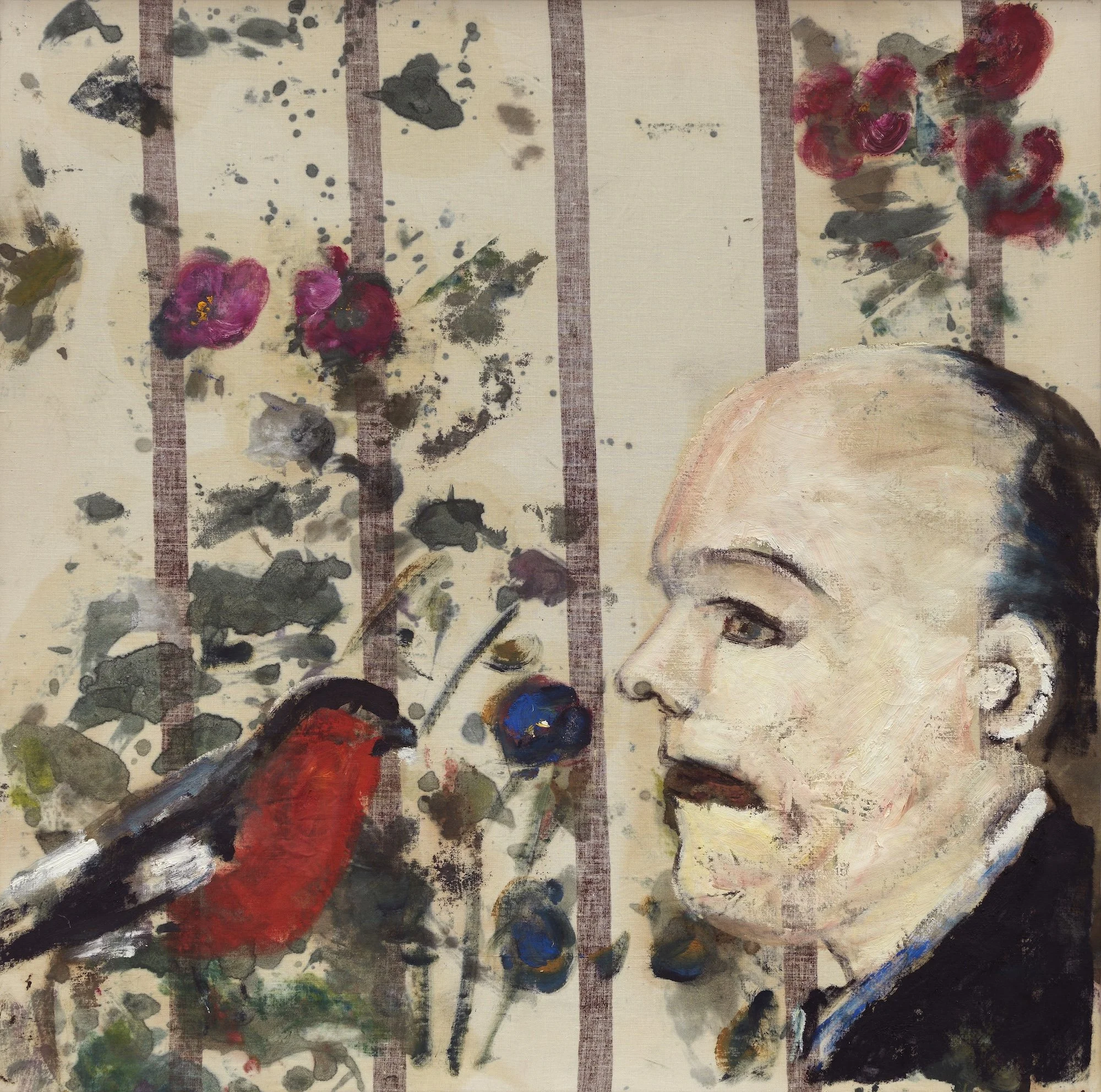

Hans Wigert, Untitled, 2015, Oil on canvas, 60 x 60 cm

Photo Per-Erik Adamsson

CAREFUL GATHERING OF IMPRESSIONS

On Hans Wigert’s Art

Text: Joanna Persman

Translation: Anna Bohman Gallery

Everything in here

is memories of time

as it was

seconds ago

Thomas Tidholm, Mixed Feelings, 2025

Hans Wigert’s art is grounded in a careful gathering of impressions, interpreted in images that are at once angular and tender. As an artist, he eludes definition. He has been called a “nature mystic,” a “melancholic,” and “a stern realist.” All of these descriptions are true, yet none of them alone is sufficient. Wigert’s pictorial world is capricious yet somehow artlessly familiar. He keeps reality within sight and dreams at close range. The urge to tell stories is always present. His adventures unfold in the borderland between the forests of northern Sweden and a fairytale realm. Scenes from Wigert’s life are interwoven with motifs from folk ballads and legends, while the depicted figures remain immune to age and decay.

In his self-portraits, we encounter the artist wearing a hat and a stained coat. The Artist (1995) is rendered in blue tones and an expressive style. More often, however, Wigert’s self-portraits revolve around what it means to be human: alone, naked, and defenseless, yet at the same time astonishingly strong.

Wigert’s painting is often associated with northern Sweden. Yet this is not where his life began. He was born in 1932 in Karlskrona. His mother died shortly after his birth. A nurse cared for him for three years while his father worked. His father was a pilot and a survivor. He crashed and survived. He crashed again and survived that crash as well. The son’s nightmare was that his debt to Lady Fortuna was so great that she would not protect them a third time. The fear of being left alone in the world was always there. Over time, art became a way of warding off anxiety. A black-and-white photograph captures Lieutenant C. G. Wigert by his wrecked airplane in the winter of 1918–19. The motif reappears seven decades later in his son’s drypoint etching Icarus (1981). Dressed in a suit, he stands there between broken wings. It was Daedalus, the father, who constructed wings of feathers and wax. It was the son who flew too high and fell.

Hans Wigert grew up in Djursholm outside Stockholm. His father was head of the air station in Hägernäs, which no longer exists. At Samskolan, things went so-so. “I was dyslexic, left-handed, and stuttered,” Hans Wigert recalled in a 1990s interview. At the time, there was little pedagogy to support children with dyslexia. However, he was talented at drawing and cut out figures that astonished his teachers. And then there was his exceptional ball sense. He achieved success in football and in Sweden’s top tennis division, competing against Sven Davidson, Uffe Schmidt, Janne Josefsson, and Janne Lundqvist. Little suggested a future artistic career. It would also be a long detour before he enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm—a detour that led via northern Sweden.

One summer, his father sent him there. He was to work at the Freshwater Laboratory while a river was being dammed. There, in Tännäs (“the shimmering”), among the mountain valley settlements around the upper reaches of the Ljusnan River and its tributaries, surrounded by vast highland forests and bare mountains, something was released within him. “All of this wonder was to be submerged. It is my sunken Atlantis,” he recalled decades later. Images began to pour onto canvases and paper. The works were sent down to Stockholm, and it was his father who delivered the application materials to “Mejan.” Hans Wigert was admitted to the Royal Academy in 1960—on his fifth attempt. It was also to his father that Evert Lundqvist wrote to announce that his son had been accepted. Lundqvist had previously been Hans’s teacher at the Gerlesborg School.

Life at “Mejan” was structured. In the mornings he painted for Evert Lundqvist. In the afternoons he drew for Bror Marklund. Evening croquis sessions followed. It was also at the Academy that Hans Wigert met his future wife, Anne. She worked part-time as a model while studying to become a dance teacher. Anne appears in many of Wigert’s works. Surrounded by flowers, she rests in the garden in a painting from 1970. The oil painting The Swimmers (1986) is like a poetic summary of their life together. With calm strokes they drift away across a lake that is sometimes shimmering, sometimes unfathomably dark. The woman as a mysterious being in close connection to nature is also one of Wigert’s favorite motifs, recurring in many variations. Perhaps, like Narcissus and Goldmund in Hermann Hesse’s novel, he was searching for the primordial mother who would fill the void left by the mother he lost so early. It may seem too easy to psychologize in this way. Yet simple explanations often prove astonishingly accurate.

The 1960s were a decade of upheaval both in world history and in art. As Gertrude Stein emphasized already in the 1930s, historiography tells what happens “now and then,” whereas storytelling tells what happens “all the time.” In that sense, Wigert was not a historian but a true storyteller who celebrated the mystery of the simple. The ordinary, the banal, became almost a ritual act. There is something unspeakably beautiful in his almost naïve way of linking the real with the otherworldly. Small children with angel wings brood in a forest. Birds with human legs and ice skates take a dance lesson on the ice. Humor flashes through at times.

Wigert also gained early recognition for his printmaking. Yet he had no revolutionary streak in his art. He did not push his experiments as far as others. Still, he broke new ground through his faithful attempt to capture each experience and its immediacy. What does it feel like to lie in the grass and sense yourself merging with the tufts, or to jump naked into a lake for an early morning swim when your skin prickles with cold? That is what his works conveyed.

In 1966, Hans and Anne Wigert bought a log storehouse from 1847. It stood in Grundsunda in Västerbotten, right by Lake Prästsjön. It cost 1,000 kronor and was actually meant to be torn down. For over thirty years, they drove there every summer. A fallen jetty lay there, claimed each year by ice, wind, and water, and each time rebuilt just as provisionally. That was the point. “The cycle of life,” Wigert used to say. The jetty appears in his paintings. Sometimes they would doze off on it. Another painting tells that story.

It was also in northern Sweden that frogs appeared in Hans Wigert’s work. He discovered one with large sores on its body. Environmental destruction had already reached that far. “Nature should not be observed—then you understand nothing. The art is to let yourself be permeated by it,” he said. It was easy to identify with animals as well. “Painted a frog, probably a self-portrait swimming in the academic world, moderately desperate,” Wigert noted in his diary in February 1991.

Hans Wigert had an exceptional ability to convey how the human being is one with nature. Naked and shivering in a forest tarn in northern Sweden, she is both its organic part and its greatest threat. In Wigert’s art, it is impossible to determine where outer reality merges into inner images. Day and night, birth and death are woven together. Icarus aims high. One is never so close to life as in the moment of death.

“I am not a philosopher. I just paint,” Wigert used to say—and he truly meant it. Painting was not an intellectual act. Its beginning lay in the ability to see. “I wonder if one hour of work at the easel requires four hours of observation,” he noted in his diary in the 1970s. “People must think I’m doing nothing when I sit down by the lake just looking or rowing. If only they knew how important it is to perceive all the small changes in light and growth.”

From these observations grew a stern yet tender visual language, one that often blurred details but was always grounded in genuine experience. Unaffected by new tastes and trends, Hans Wigert continued throughout his life to create by ear, by instinct. It was his modesty, free from all search for effect, that made him a great artist. To love Wigert’s work, one need not know much about art. It is enough to be curious about life.